Part 1: The prelude, from rule-based to learning algorithms

Last updated December 1, 2025

Machine Learning

Guide Parts

This series is about neural networks, but before we get there, let me take you on a short detour, a bit of a story about how learning algorithms, and eventually neural networks, came to be. Why start here? Because it is hard to appreciate what problem neural networks solve without first seeing what came before them. Please, stay with me.

Imagine you want to teach a computer to identify spam emails. You start simple. You write a small rule:

if "win" in subject:

mark_as_spam()

It works for the most obvious cases. Then a new email arrives:

Subject: You have won a brand-new tablet!

Body: Click here to claim your prize today.

This one slips through. The word “won” is not the same as “win,” so your rule misses it. You patch the system:

if "win" in subject or "won" in subject:

mark_as_spam()

Now it catches both cases. So far, so good. Then, more spam appears with new tricks. You expand your rule:

SPAM_KEYWORDS = {"win", "won", "prize", "jackpot", "lottery", "free", "claim"}

if any(word in subject for word in SPAM_KEYWORDS):

mark_as_spam()

This works until a legitimate message shows up in someone’s inbox:

Subject: Confirm your email to activate your free account

Body: Here is your verification link

Your system blocks it because of the word “free.” So you add another rule to fix the false positive:

if sender in TRUSTED_SENDERS:

mark_as_not_spam()

Now you have two rules: one to catch spam, one to let certain emails through. But new emails keep arriving with unusual formats, harmless promotions, or clever phrasing you did not anticipate. Each time a new exception appears, you write another rule.

Each fix creates room for another failure. Slowly, your simple script grows into a web of conditions and exceptions. Even with all that effort, spam still sneaks through, and legitimate messages still get blocked.

That is the reality of rule-based programming. It works only when the world behaves predictably, when every possibility can be written down as a rule. But email is messy. Language is flexible. People phrase things in thousands of ways. No matter how many rules you add, something always escapes.

And that frustration led to a simple but revolutionary idea.

Enter learning algorithm

After wrestling with the endless rules in our spam filter, researchers began thinking differently. Instead of writing out every possible case by hand, they asked a simple question: What if we show the computer thousands of examples, and let it find the patterns on its own?

This idea marked the beginning of machine learning, a new way of programming where computers learn from experience rather than explicit instructions. The logic flipped. Instead of humans writing all the rules, the algorithm analyses data, identifies patterns, and generates rules automatically.

In our spam example, rather than adding new conditions every time a tricky email slips through, a learning algorithm looks at many labelled messages, “spam” or “not spam”, and learns which patterns matter. It tests hundreds of possibilities, measures its mistakes, adjusts itself, and progressively becomes better at the task.

Instead of writing hundreds of rules by hand, the paradigm shifted. Humans now have to write one single rule: the rule behind the learning algorithm. This is the core idea behind learning algorithms. And to understand how they work, we need to look inside.

The anatomy of a learning algorithm

Most learning algorithms, no matter how different they seem, follow the same basic structure. To make this concrete, let us switch to an example that is easy to visualise. Imagine we want to train a model to recognise whether an image contains a cat.

- The algorithm takes an input X (an image).

- It returns an output Ŷ (the probability that the image contains a cat).

- During training, it knows the true answer Y.

Inside the model, three essential parts work together to turn X into Ŷ.

Loss function: How wrong am I?

Compares the prediction (Ŷ) with the true answer (Y) and tells the algorithm how far off it was.

Optimisation criterion: What’s the goal?

Defines the learning objective. For example, “minimise the average error across all training images.”

Optimisation routine: How do I improve?

Once the model knows how wrong it is and what goal to chase, it must figure out how to improve.

It adjusts its internal parameters and loops through the process: Predict → Measure → Improve → Repeat.

A final note

This is the general structure that most learning algorithms share, but the specific details differ:

- The loss function changes depending on the problem (e.g., squared error vs. cross-entropy).

- The optimisation criterion may define different goals (e.g., minimise error, maximise likelihood).

- The optimisation routine can vary too (e.g., gradient descent).

Traditional machine learning

When people refer to traditional machine learning algorithms, they mean algorithms that learn patterns from well-defined features. A feature is a piece of information that you can measure and write down in a structured way.

A feature has a precise meaning, a clear scale, and a clear relationship to the thing you want to predict. For example, imagine you want to predict a house's price. Each home has measurable attributes: size, number of bedrooms, location, and age. These are features. You can represent each house as a row in a table.

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Size | 120 sqm |

| Bedrooms | 3 |

| Location | Suburb |

| Age | 5 yrs |

You can then train a model, such as linear regression, to learn patterns like: “Larger houses in certain neighbourhoods tend to sell for more.” Here, the problem is well-suited to traditional ML because the relationship between the features and the outcome is clear.

- Increase the size, and the price tends to rise.

- Increase the distance from the city centre, and the price tends to fall.

These patterns are logical and consistent; when one value changes, the effect on the outcome is predictable. They directly influence the outcome in ways we can reason about. The features themselves are easy to define because they have been manually extracted and already exist as columns in a dataset.

Even if we can get a sense of how the attributes would affect the price, what makes machine learning powerful is that it does more than confirm what we already know.

- It quantifies how much each feature affects the final price. Not just that size matters, but by how much.

- It uncovers interactions humans do not always see, like how a garden dramatically increases value in the city centre but less so in the countryside. This kind of relationship is not always obvious, but the model discovers it by studying the data.

Traditional ML algorithms work best when three conditions hold.

- The features are clear: You can list out the attributes that matter, measure them reliably, and store them in a structured format.

- The data behaves predictably: The relationship between the inputs and the output follows patterns that can be captured with simple mathematical rules.

- The problem can be expressed in a structured form: meaning that every observation example, can be reported as a row with multiple columns in a table.

Traditional ML algorithms depend entirely on a clear list of features we can define.

So, as long as you can list out the attributes that matter and measure them

reliably (one row = one observation), well-implemented traditional machine learning

algorithms will likely find patterns within them. When the data becomes messy, unstructured,

or challenging to describe (e.g., images), the list of features becomes much harder to write.

Some problems refuse to fit into neat columns. This becomes clear when we turn our focus to

the use case we will follow for the rest of the series.

The feature problem

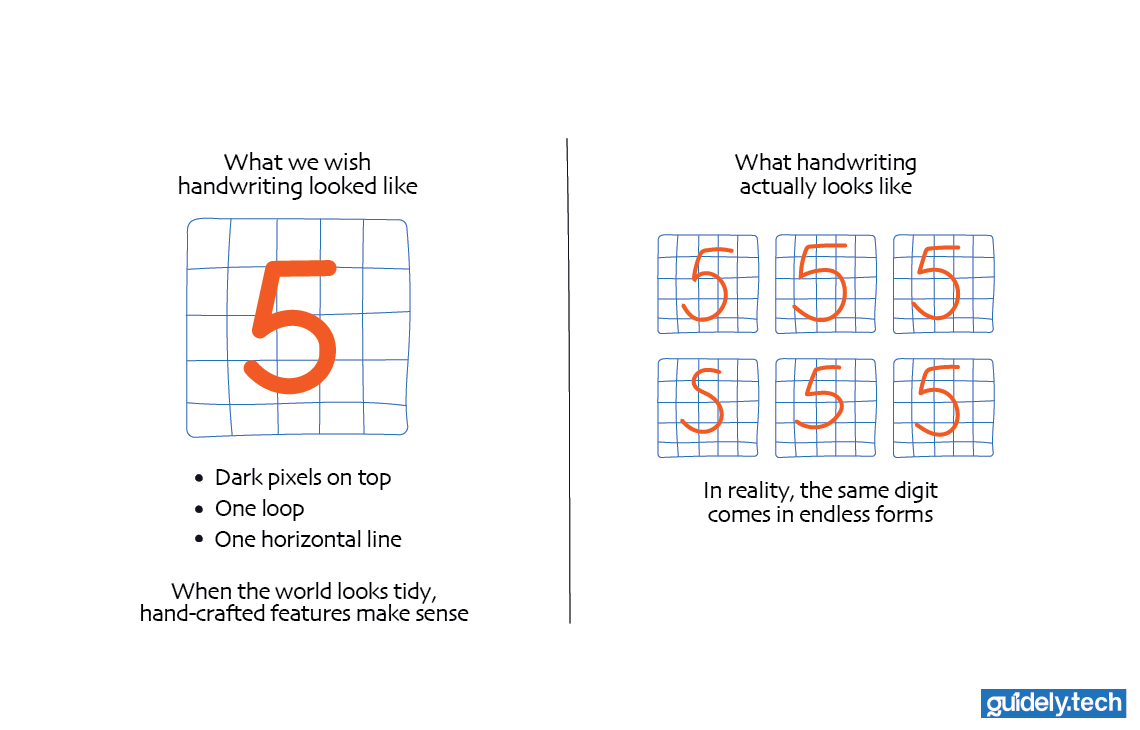

Now imagine switching from house prices to handwritten digits recognition. This time, there are no tidy columns or clean numbers; just thousands of raw pixels forming shapes that vary widely from person to person.

How do you describe the features of a handwritten digit? You might try defining them manually:

- The number of dark pixels in the top half of the image

- The ratio of vertical to horizontal strokes

- The curve along the edges

- The size of the white space inside loops

At first, this feels doable. But then reality steps in. Every person writes digits differently. Some press harder. Some write quickly. Some tilt their pen. Even the same person never writes the same “5” twice. Soon, the number of possible features explodes. What began as a neat list turns into hundreds of vague measurements that fail to capture what actually matters.

Worse still, these features do not always combine in simple ways. A “5” can look like an “S,”

and a small smudge can turn a “0” into a “6.” The relationships between pixels are not straight

lines anymore. They twist, overlap, and interact in ways traditional algorithms cannot easily follow.

This complexity breaks the assumptions on which those algorithms depend. They expect the world to behave like a chart: smooth, consistent, and measurable. But handwriting is more like art; full of subtle variation and personal style.

Traditional algorithms can only learn from the features humans provide. If those features fail to describe the actual pattern, the algorithm stops learning, no matter how much data you feed it. In other words, the learning ends where human intuition ends.

Why this mattered

The challenge was not that traditional algorithms were bad; they were brilliant within their limits. They made it possible to predict weather patterns, detect fraud, and recommend movies. But as soon as the data became high-dimensional (like an image with thousands of pixels) or unstructured (like text or sound), the traditional methods struggled.

The world needed a new kind of learning system, one that could discover features on its own, without depending on humans to define them first.

The turning point

This search led researchers to look at the ultimate learning machine: the human brain.

If a biological system could learn to recognise faces, sounds, and symbols directly from sensory input, perhaps computers could do the same. That idea led to the next great leap in the evolution of learning algorithms: the neural network.

Up next

In the next part, we will explore what neural networks are, how the brain inspires them, and why they have become the foundation of modern AI. We will also see how they overcome the limitations of traditional ML algorithms by learning not just from data but from its raw, unstructured form.

Read previous part

Neural Networks - An intuitive and exhaustive guide

Read next part

What are neural networks, really?

Enjoyed the read? Help us spread the word — say something nice!

Guide Parts

Enjoyed the read? Help us spread the word — say something nice!

Guide Parts