What are neural networks, really?

Last updated December 15, 2025

Machine Learning

Guide Parts

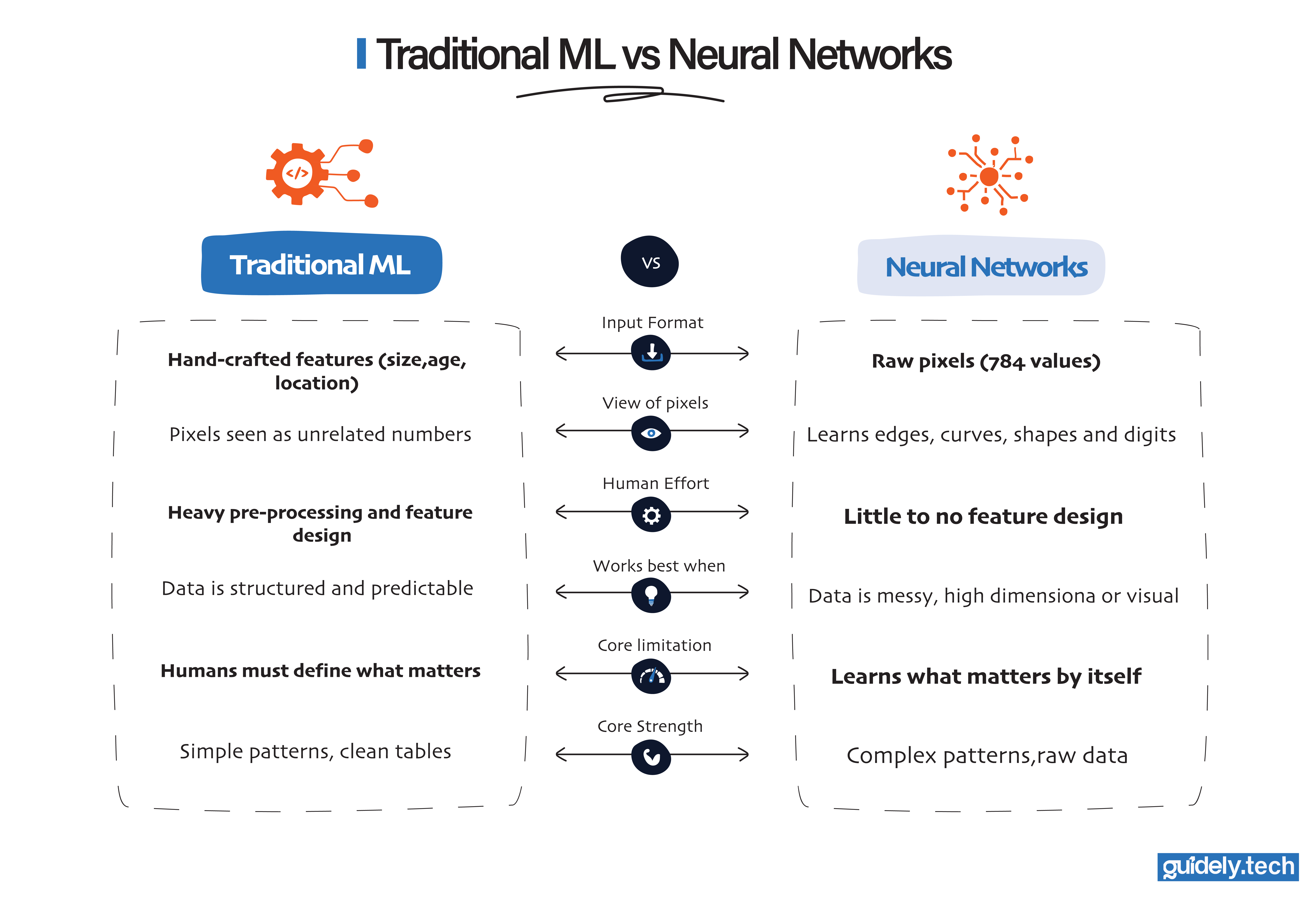

In the prelude, we saw that rule-based systems break when the world gets messy. Traditional machine learning struggles when we cannot describe the world with tidy features. Handwritten digits exposed this clearly.

No matter how many features we tried to hand-craft, they never fully captured the endless ways people write a simple “5”. Researchers asked a new kind of question: Instead of telling the computer which features matter, can it discover them for itself directly from the raw data?

That question led to neural networks.

The idea that changed everything

Traditional ML expects us to deliver a clean feature table. For house prices, this works.

- Size

- Bedrooms

- Location

- Age

We can write these as numbers in columns. The model then learns patterns that link those numbers to the price.

Handwritten digits are different. At the start, there is no feature called “loop at the top” or “curve in the middle”. There is only a grid of pixels. For a 28×28 grayscale image, that is 784 numbers.

Traditional ML models can work with raw pixel values, but they usually require substantial human intervention before they perform well. In theory, you can feed a model like logistic regression all 784 pixel values from a 28×28 handwritten image. It will train and make predictions. But without extra guidance, the results are often poor. Why?

Because traditional models do not naturally “see” structure in images. To them, each pixel is just an isolated number. They do not recognise that:

- Clusters of pixels form edges

- Small arcs form curves

- Certain orientations matter more than others

So humans must step in to help the model understand the image. This often means adding several layers of preprocessing. Only after this extra work does the traditional model begin to recognise digits reliably. In other words:

- The algorithm is learning the pattern

- But humans are hand-crafting the clues it needs to succeed

That is the core limitation. As data becomes more complex, the amount of manual feature engineering grows rapidly. Some problems, such as handwritten digits, faces, or images, contain patterns that are too subtle and varied for humans to extract by hand. This is where neural networks changed everything.

Instead of relying on humans to design appropriate features, a neural network learns them directly from raw pixels. That ability to learn features automatically is what allowed neural networks to overcome the limits of traditional machine learning.

With a neural network, instead of saying, “Here are the features, please learn from them,” we say: “Here are the pixels and the correct label. Learn both the features and the patterns by yourself.” This shift is the heart of what makes neural networks different.

A quick look at the brain for inspiration

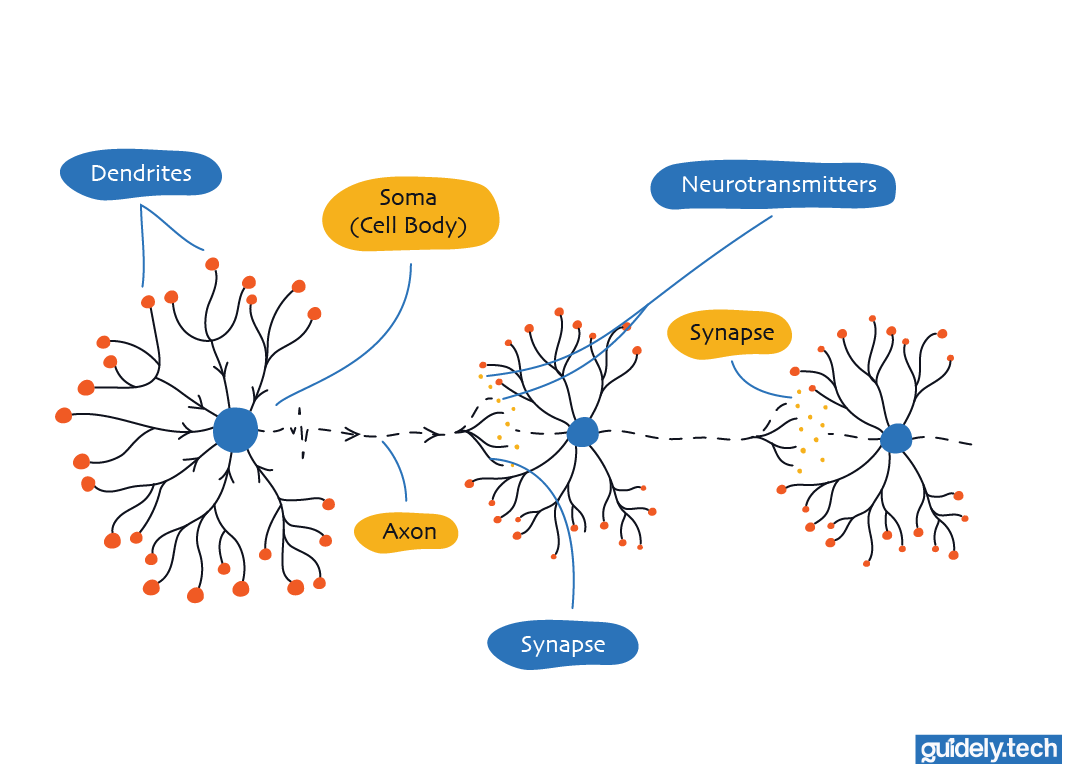

The name “neural network” comes from the brain, but the connection is a loose inspiration rather than an exact copy. Inside your brain, billions of tiny cells called neurons communicate with one another.

- A neuron receives tiny electrical pulses from other neurons.

- These pulses accumulate, like drops filling a small cup.

- When the cup reaches a certain level, the neuron fires. It sends its own electrical pulse to other neurons.

This simple cycle, receiving a pulse, checking if it’s strong enough, and firing, is how real neurons pass information through the brain. No single neuron understands the world. Understanding comes from many neurons working together in layers. Researchers asked a simple question: What if we could build a simplified version of this idea for computers?

- Tiny units (artificial neurons) that receive numbers

- Each unit makes a small decision

- Many units connect together in layers

- More interconnected units allow to learn more complex world representations

This led to the idea of artificial neurons and layered networks.

We will examine these neurons in the next part. For now, we care about what this structure looks like and what it allows a network to do.

From raw pixels to understanding

Let us return to our handwritten digit example. We give the network:

- Raw pixel data from a scanned, handwritten image of a digit.

- The correct digit as the label (5, for example)

The network does not start with any built-in knowledge of what a “5” looks like. So how does the network move from these raw pixels to recognising the digit?

The layered architecture

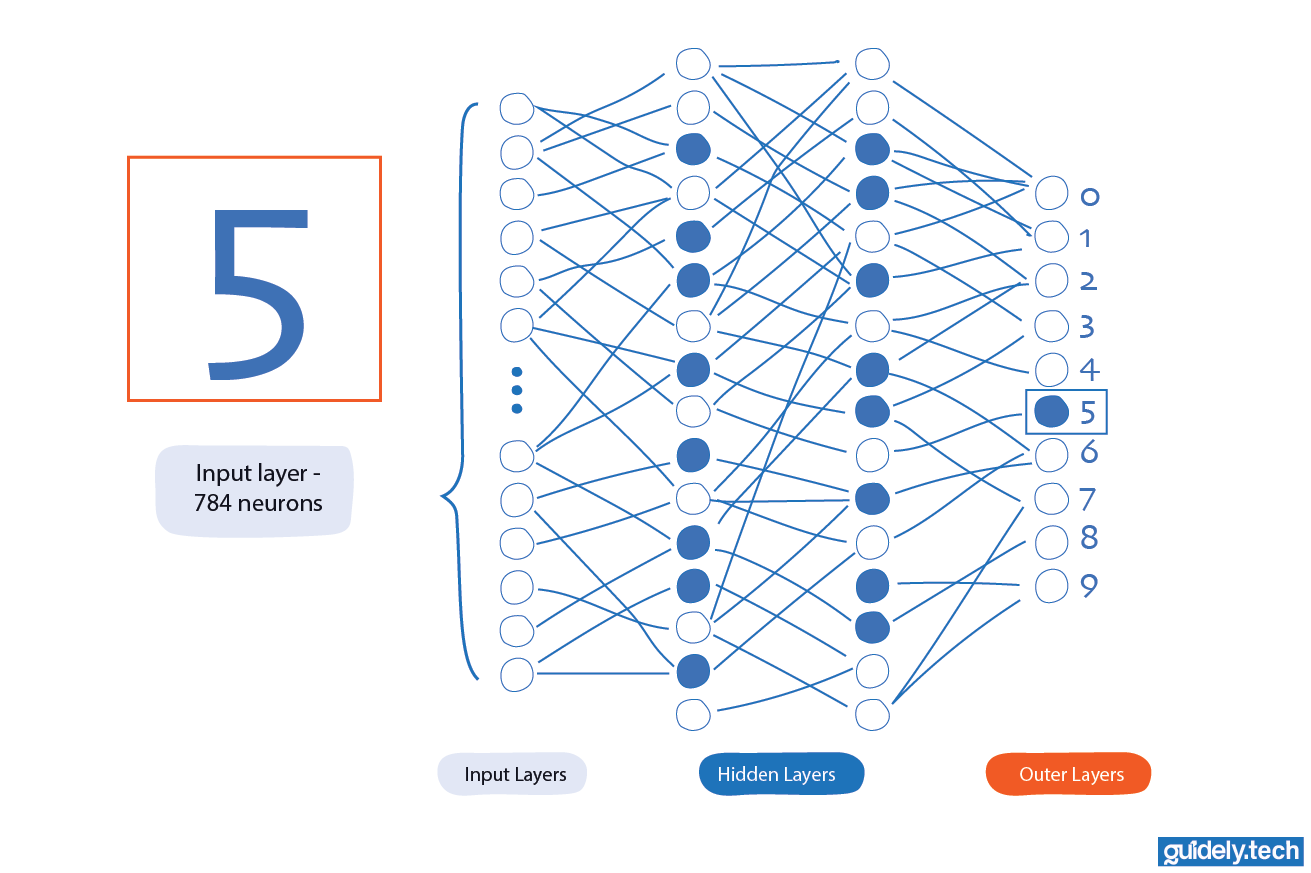

All neural networks follow a layered architecture:

- One input layer

- One or more hidden layers (between the input and output layers)

- One output layer

The design of the input and output layers is often the easiest part of a neural network. Take our handwritten-digit example. The network receives an image of a digit between 0 and 9. In our case, a 28×28 handwritten “5”.

A 28×28 greyscale image contains 784 pixels. So we represent the image as 784 numbers, each between 0 and 1, depending on how dark or light the pixel is. These 784 values become the 784 input neurons of the network.

On the other end, the output layer contains 10 neurons; one for each possible digit from 0 to 9. After processing the image through its layers, the network produces a value for each output neuron. The rule is simple:

- The neuron with the highest value (between 0 and 1) is the network’s prediction.

- If the “5” neuron has the strongest signal, the network says: "This image is a 5."

From the outside, it looks almost trivial. But everything interesting happens between the input and the output layers. Between these two layers are the hidden layers.

They are called “hidden” because we never see their outputs directly. Their job is to take the raw pixels and slowly transform them into useful internal representations. In this guide, we will work with shallow networks, meaning networks with just one or two hidden layers. Deep neural networks stack many more hidden layers, but the underlying principle is the same: Each hidden layer learns a slightly more abstract feature than the previous layer.

What we hope to achieve with a layered architecture

When you hear “neural network,” it is easy to picture a mysterious black box. But at a high level, the big idea is surprisingly simple. A neural network is built in layers because each layer has a different job. Each one helps the network take one small, understandable step toward recognising something much more complex, like a face or a handwritten digit.

Let us stay with our running example: recognising a handwritten 5.

Imagine the network has two hidden layers between the input (raw pixels) and the output (0–9). What are these hidden layers doing? Think of them like teams, each handling a different level of difficulty.

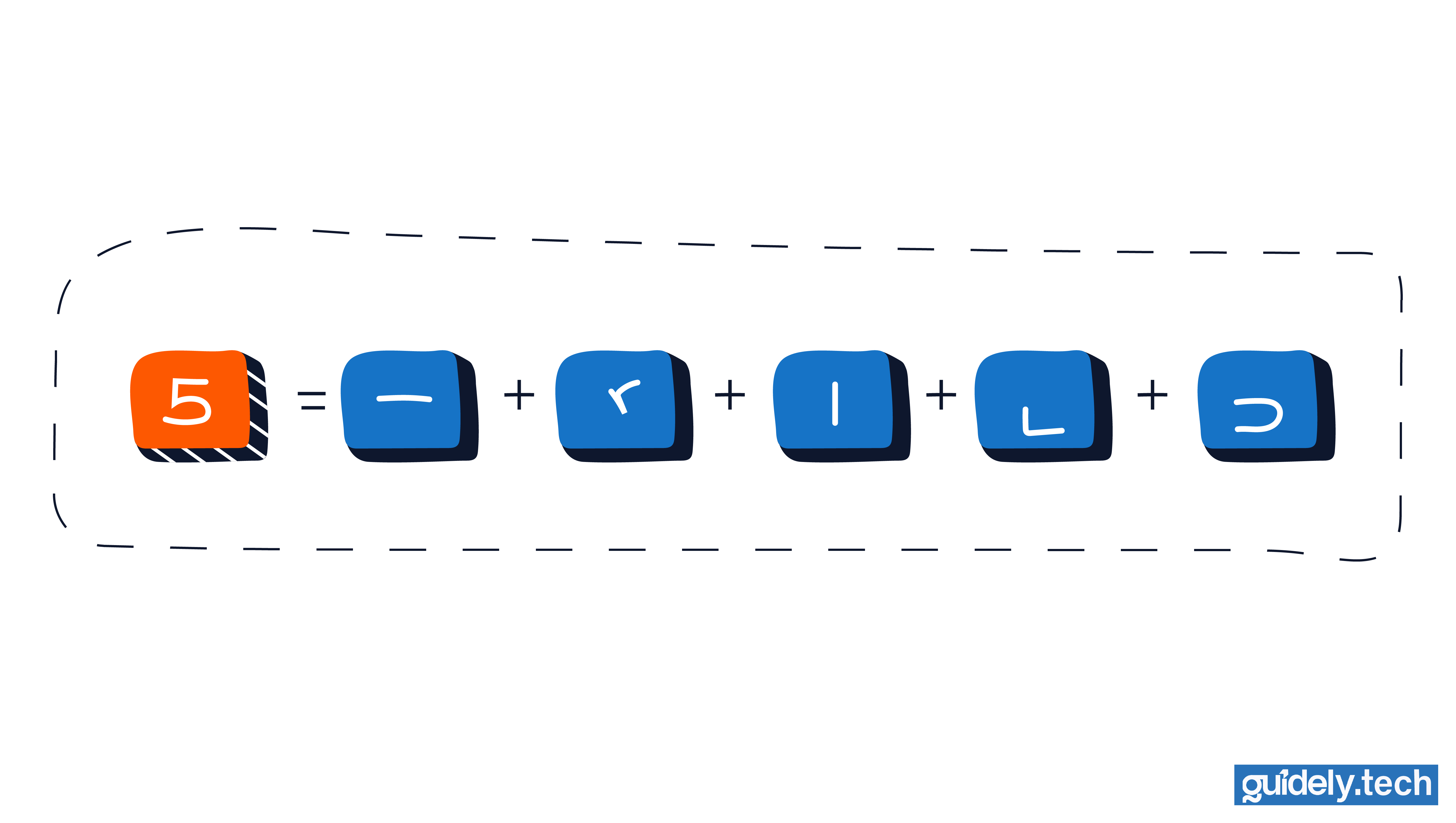

Layer 1: Detect edges

The first hidden layer focuses on the smallest, simplest clues.

If we zoom in on a handwritten 5, the shapes we see are usually some combination of:

- a short horizontal stroke at the top

- a vertical edge on the left

- a curved stroke forming the bottom

- a sharp bend where the top stroke drops downward

- a small hook-like turn where the curve meets the lower part of the digit

In this layer, each neuron becomes sensitive to a tiny pattern in a small region of the image. For example:

- Neuron 1 fires when it sees a short horizontal stroke

- Neuron 2 fires when it sees a left-side vertical edge

- Neuron 3 fires when it sees a sharp downward bend

- Neuron 4 fires when it sees a curved lower stroke

- Neuron 5 fires when it sees a hook-like turn

When a neuron “fires,” it simply means: “I think the pattern I’m responsible for might be present in this image.”

It is just a number becoming large enough for the neuron to pass a signal forward.

At this point, the network still doesn’t know anything about digits.

It is only detecting very small building blocks.

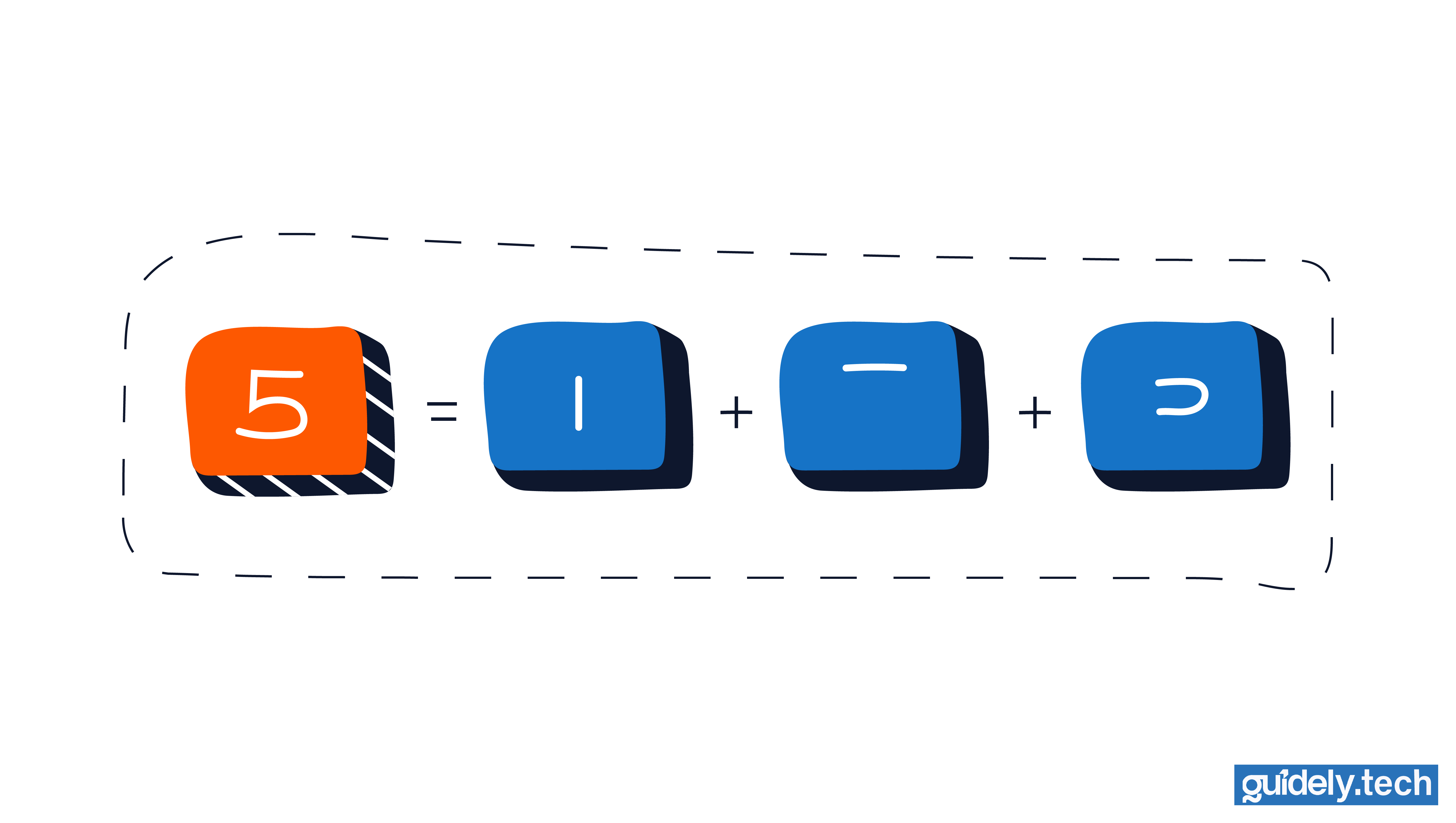

Layer 2: Detect bigger parts

Now imagine the second hidden layer receiving dozens of tiny signals. If the first layer sees puzzle pieces, the second layer tries to group those pieces into larger, recognisable parts of a 5.

For example:

- Neuron 1 fires when it detects “a short horizontal stroke + a left vertical edge” → the top-left corner of a 5

- Neuron 2 fires when it detects “a left vertical edge + a bottom-left curve” → the left spine flowing into the bottom curve

- Neuron 3 fires when it detects “a bottom-left hook + a sweeping curve” → the bottom bowl of a 5

This layer is no longer dealing with “edges.” It deals with meaningful sub-shapes. At this stage, the network is beginning to form an internal, layered understanding of the digit. Not because we told it to find these shapes, but because recognising these shapes reduces its mistakes. Whatever helps reduce error is what the network eventually learns to detect.

Output layer: Detect whole digits

Finally, the output layer receives signals like:

- “Top bar detected”

- “Bottom swirl detected”

- “Left spine detected”

The output layer’s job is simple: Which digit (0–9) do these parts most strongly suggest? If the neuron for 5 receives the strongest combination of signals (greater than 0.5), the network says: “This image is a 5 with 70% likelihood.”

Answering our question more directly, we might hope the network behaves something like this: When an image comes in, the first hidden layer picks up tiny clues: small strokes, little bends, short edges, etc. Each neuron lights up when the pattern it cares about seems to be present.

Those signals then flow into the next layer. Here, neurons look for bigger, more meaningful shapes built from the earlier clues: A corner, a curve flowing into a hook, a top bar sitting above a vertical spine. If enough of the right pieces appear together, these neurons fire too.

Finally, the output layer sees these larger shapes and chooses the digit that fits them best. If the parts line up, the neuron for 5 fires the strongest.

This picture is not an accurate depiction of how all neural networks truly organise their knowledge. It is simply a helpful way to think about what we hope the layers learn as the network improves; an intuition we will revisit once we explore how training actually works.

Let’s pause and reflect

It is important to pause here and be honest.

The picture we have just painted, edges in the first layer, parts in the second, full digits at the end, is a mental model. It is a useful way to build intuition, especially for image tasks where we can literally see edges and shapes. But neural networks are not limited to images. They work on text, audio, tabular data, signals, and many other forms of information. In those cases, there are no visible “edges” or “loops” to point at.

This naturally raises a deeper question: What is a general, reliable way to think about what layered architectures are doing, regardless of the type of data?

To answer that, we must gently shift our perspective away from shapes and pixels, and toward a more mathematical view of neural networks. This view helps us understand what each layer contributes, why stacking layers matters, and how networks learn useful internal representations even when those representations are not visually interpretable.

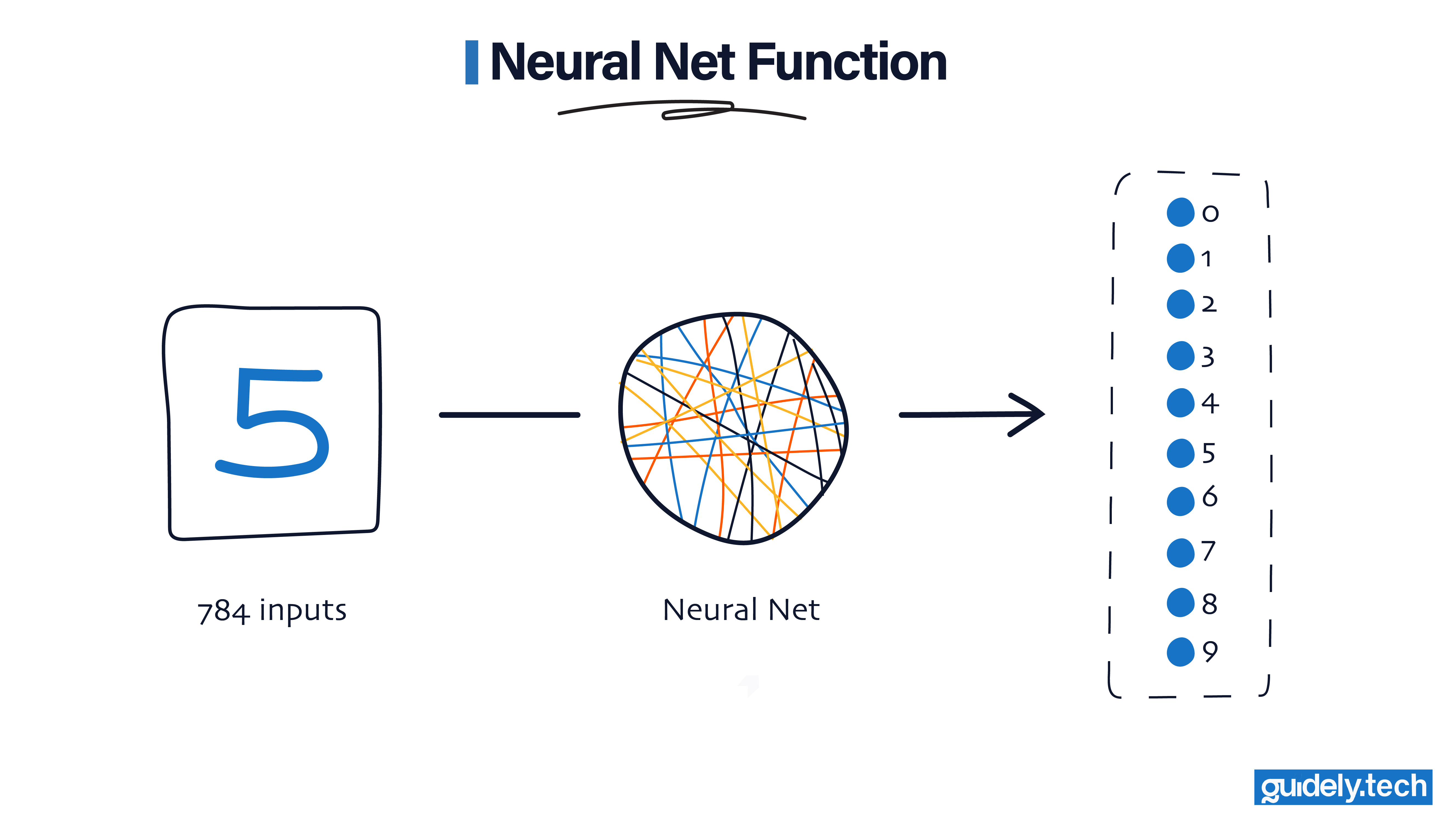

A neural net is just a function

At its core, a neural network is a function. Before we go any further, let us briefly ground ourselves in what that means.

A function is simply a rule that takes something in and produces something out.

- You give it an input.

- It applies a transformation.

- You get an output.

In our case:

- Input: 784 numbers representing pixel brightness.

- Output: 10 numbers representing how likely the image is to be each digit from 0 to 9.

So far, this sounds no different from traditional machine learning. The difference lies in how the transformation is built.

A single layer can only do simple things

A single neural layer takes a list of numbers and applies a simple rule to them. Mathematically, it can only learn functions that separate things with straight or gently curved boundaries. Here is a concrete way to picture it:

- If you give a single-layer network exam scores in Math and English, it can learn a rule like “Students above this line pass”.

- But if the real rule is messy, like “Pass if Math is high unless English is extremely low, except when…”, one layer cannot bend itself enough to capture that pattern.

This limitation becomes very obvious with something as complex as a handwritten 5. A single layer tries to jump from 784 raw pixels → prediction in one step. That jump is too big. The relationship between pixels and the digit is far too tangled for a single-layer model to untangle.

Layers fix this by working in stages

The key mathematical idea behind neural networks is composition. Instead of jumping directly from pixels to prediction, a neural network builds understanding in stages:

- One layer learns a simple transformation.

- The next layer transforms the output of the previous layer.

- More layers keep building on top of one another.

You can think of it this way:

- Layer 1 can handle simple patterns.

- Layer 2 can handle patterns made from those patterns.

- Layer 3 can handle even more complex combinations.

This is true not just for images, but for any kind of data. Stacking many simple transformations gives the network the expressive power to model patterns that would be completely unreachable with a single layer.

Back to our handwritten 5 example

Layers allow the network to transform the data gradually:

- Raw pixels → something a little more interpretable

- That intermediate representation → something even more structured

- Eventually → something that makes “5 vs 3 vs 8” easy to separate

No single layer knows what a “5” is. But after several small transformations, the network creates an internal representation where the digit becomes clear. That is the core idea: Understanding does not live in one place. It emerges from the composition of many simple pieces.

Why this matters beyond images

The image intuition (edges → parts → shapes) is just one way to understand this. In other domains:

- Speech models build layers of sound patterns.

- Language models build layers of meaning.

- Fraud detection models build layers of behavioural patterns.

The principle is the same: Each layer transforms the data into a representation that is easier for the next layer to work with.

That is why layered architectures matter.

What we have not yet explained

At this point, you might be wondering:

- How does a neuron know which pattern to detect?

- Who decides which neurons fire and when?

- How do these layers actually learn?

- Where do weights and biases fit into this picture?

- What does “firing” mathematically mean?

- How does the network adjust itself when it makes a mistake?

These are precisely the questions we answer next.

Up next: inside a neural network

In this part, we stayed at the big-picture level. We focused on what neural networks are and why they matter. To really understand how they learn, we now need to zoom in.

In Part 3: “Inside a neural network: neurons, weights, biases, and activation functions”, we will open the black box and look at:

- What a single artificial neuron does

- How weights and biases control a neuron’s behaviour

- Why activation functions are necessary for learning complex patterns

- How these pieces combine to turn raw pixels into understanding

Once you see how a single neuron behaves, the entire neural network will feel far less mysterious.

Read previous part

Part 1: The prelude, from rule-based to learning algorithms

Read next part

Inside a neural network

Enjoyed the read? Help us spread the word — say something nice!

Guide Parts

Enjoyed the read? Help us spread the word — say something nice!

Guide Parts